by Florian Bayer

Being part of a traumatized and displaced diaspora, Syrian Armenians refuse to be labelled as “refugees” back in the home of their ancestors, Armenia. Most are here to stay, since the grueling war in Syria goes on, but also since the more than ten thousand recent settlers are best possible integrated in Yerevan.

“Aleppo Shopping Center” reads a sign at the Republic Square metro station in Central Yerevan, and what you read is exactly what you get: a small mix of spice shops, bakeries, a joint with cheap jeans and t-shirts or a hairdresser, and all praise their products and services in Arab letters: they are predominantly run by Syrians. Armenian Syrians, to be precise, since a total of around 20.000 Syrian-born members of the big and regionally widespread Armenian diaspora moved only recently, during the ongoing Syrian Civil War, to Armenia.

Finding a new home

Dalida in the bakery

“I came 2014 with my relatives – with high unemployment, wages of only about 200€/month and expensive housing, life here is hard – but we can make it”, says Syrian-born Dalida (53), who runs a small bakery. She has no kids, and with her earning she and her husband can get by one way or another.

Her colleague Greta (name changed) from the shop next door, on the other hand, has no complaints about business: “We have products from Syria, Turkey, the UAE, Iran. Especially our spices are very popular”, says Greta. Her husband owns the small shop in the metro passage, and indeed every minute the door to the narrow metro-passage opens again and people get in line to buy a handful of exotic spices. All her family and friends escaped from Syria to Yerevan, where most of them stay until now. Only her kids found a new home in Sweden and Canada, at least for now.

There are essentially two groups of incoming people from Syria, says Anna Dahlaryan, who works for the Austrian Development Agency (ADA). “The first group, among them many more affluent people, came at the beginning of the war, thinking they would just be here for some weeks until the worst is over – which most unfortunately turned out to be wrong. The second one came subsequently in the years 2014 and 2015 and was strongly in need of help”, says Dahlaryan.

Traumatized by losing family and friends and often with nothing more but a small suitcase in their hands, they had to start entirely from scratch. For ADA humanitarian aid was the first step to help, before later enabling the incoming people to continue working in their former profession by providing cheap credits in order to open up their own businesses in Armenia. ADA-projects co-founded by the EU as well as UNHCR, Caritas and Red Cross enabled many refugees to open up Syrian restaurants, handicraft businesses or small shops. “The general attitude towards Syrian Armenians was very positive. There was a strong consensus in society that they should be repatriated as fast and thoroughly as possible”, says Dahlaryan.

Also 22-year old Aram (name changed), who himself came from the Syrian city of Latakia at the Mediterranean Sea, speaks about the enormous helpfulness of both the Armenian people and the state. Aram came with 17 years to Yerevan, without having friends or families here: “I had to start from scratch. The first two or three months were very difficult for me, since I did not know anybody and life was much harder here than in Syria”, he says. After having started his new study in business administration, however, did he do much better and quickly made friends among native Armenians. Via a study-exchange program he got into touch with the organization Caritas, for which he subsequently worked as a volunteer translator from Arab to Armenian. The commitment paid off, since he soon will start a paid full-time position there.

Easy integration

The integration here was no problem for him, as Aram explains, since traditions, culture and – to a large extent – language are the same: “In Latakia, I have learned Western Armenian from kindergarten on. We had television from Armenian channels, so we even knew some Eastern Armenian.”

The different dialects derive from the history of much of the global Armenian diaspora, especially in this region: Starting 1915, Turkish elites committed a genocide against the Armenian minority living in the region at the turn from the Osman Empire to the Turkish republic. First by killing almost 300 Armenian intellectuals in Istanbul, only before conducting large-scale persecutions and massacres of thousands of Armenians in former Western Armenia, a territory which was subsequently and up until today was seized by Turkey.

Even to this day, Turkish officials and many intellectuals deny any participation in taking part in these systematic murders. Most international experts however agree that this was one of the first ethnic cleansings in history, decades before the term “genocide” was even coined. Also the Armenians strive for international recognition of what happened from 1915 to the early 1920s, and for example paid thankfully attention when Germany along with other countries recognized the violent crimes that were done to Armenians, even without using the words “Turkish” or “genocide”.

History still matters

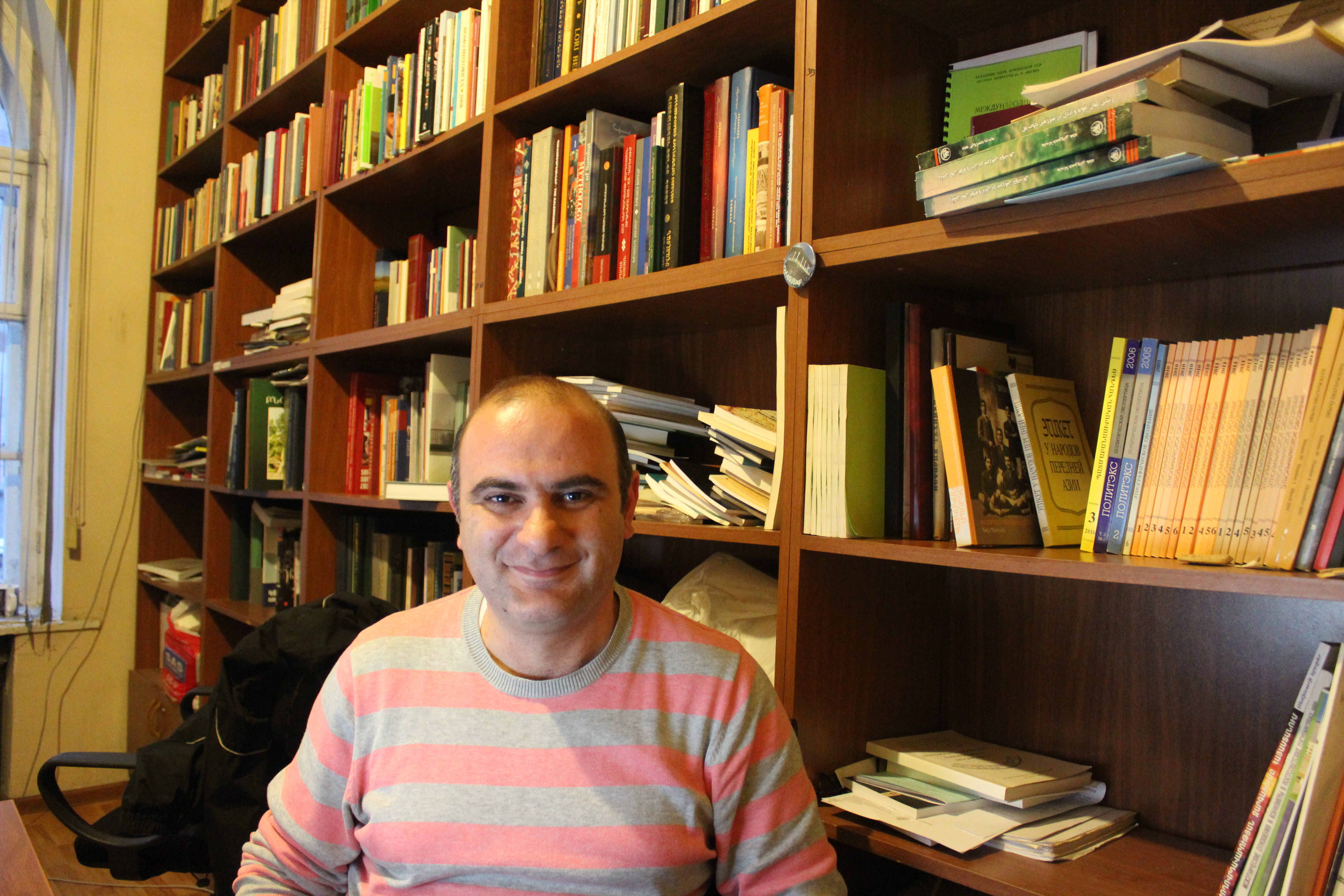

When living or just travelling through Armenia as a visitor, one cannot help but be confronted with this topic on a daily base. Be it by coming across the topic of the 3-million-strong Armenian diaspora, be it by visiting the impressively elaborate Armenian Genocide Museum “Tsitsernakaberd”, be it by talking to youths or also experts on this field such as Arsen Hakobyan, anthropologist at Yerevan State University and the Armenian Academy of Sciences. “There was already an Armenian minority in Syria in the ancient world as well as in the middle age. The most recent population, however, were the ancestors of the genocide-survivors”, Hakobyan says. He wrote numerous research papers about memory politics and identity, as well as oral interviews with people who left to Yerevan.

Arsen Hakobyan

His conclusions? “It was quite obvious for Syrian Armenians to come “back” to Armenia in the course of the Syrian war – to come “home” so-to-say. It was the same culture, almost the same language and their main identity”, Hakobyan elaborates about the Armenian minority in Syria. Helpful, as he explains further, was certainly the fact that the Armenian government made immigration as easy as possible [not the least because of the fact that many young Armenians leave the country for better job chances and wages abroad, that is].

“Already for longer, it was possible to have a dual citizenship in Armenia. Additionally, the government decided to give the Armenian passport out easily, even from abroad”, says Hakobyan. Consequently, already from an early stage of the war it was possible to apply for citizenship not only in Yerevan, but also from the consulates in Aleppo [where by far the largest Armenian minority of about 60.000 people was living], Damascus and in Lebanon’s Beirut. In buses via Turkey and Georgia, but also in flights from Beirut, it was easily possible for Armenian citizens to reach Yerevan.

Preserved Armenian culture

By doing his research, several Syrian Armenians said that they always felt more Armenian than Syrian, explains Hakobyan: “Weld together by the experience of displacement and murder, the preservation of Armenian customs, religion and traditions was and is alive until today, even 100 years after the genocide.” Not only were the [Christian] Armenians the only group which had minority rights such as religious institutions and own schooling in [predominantly Muslim] Syria, they were also well respected for being good merchants and highly skilled craftsmen.

Aleppo NGO – one of many NGOs helping Syrian Armenians in Yerevan

The war eventually changed everything, though, and at least 10.000, perhaps even twice as many, Syrian Armenians now build on their new future in Yerevan or other Armenian towns and cities. “We never considered ourselves as refugees though, also were not treated as such”, 22-year old Aram says resolutely. Much rather he and all others interviewed for this story, describe their going to Armenia as “coming home”- home to a safe place and to the homeland of their ancestors.

Florian Bayer (27) is a freelance journalist based in Vienna. He studied journalism, history and philosophy and has special interest in society, culture and politics in Eastern Europe (especially Poland) and far-right populism on the rise in Europe and elsewhere.

Florian Bayer (27) is a freelance journalist based in Vienna. He studied journalism, history and philosophy and has special interest in society, culture and politics in Eastern Europe (especially Poland) and far-right populism on the rise in Europe and elsewhere.